Early settlers often built communities near rivers for practical reasons such as for a fresh water supply and transportation. During the Industrial Revolution, rivers were vital for transporting goods including coal and iron. Today they remain equally as important, but the reasons have changed. Most rivers are now more about providing space for wellbeing and recreation.

Carter Jonas has worked on several projects reconnecting people to waterways and recently created a regeneration plan for the Vale of White Horse District Council for Abingdon-on-Thames. Its particular focus was the regeneration of the city centre and its relationship with the River Thames, which provided the opportunity to breathe life into the town. Glen Richardson, Associate Partner in Masterplanning & Urban Design at Carter Jonas was part of the team that created the Abingdon town centre masterplan, the Central Abingdon Regeneration Framework (2023). Here he explains why rivers are so important and how it is possible to overcome challenges to ensure they can be part of a regeneration scheme.

Glen explains, “Part of the aim of the Central Abingdon masterplan was to celebrate the town’s link to the River Thames, use it to highlight Abingdon’s rich culture and heritage, as well as make it a more attractive space for residents and visitors.”

What rivers bring to a community

“It is important to encourage the public to use the River Thames better because it’s such a lovely, natural resource for the people of the town and visitors. We all want access to nature. We all want to be able to take time out to touch base with nature, and water is such an important resource for us in some many ways, including culturally.

“In Abingdon, for example, there is a need to reconnect because, despite the attractive green spaces and historic buildings along parts of the riverside, the main town centre was built north, away from it. So you don't really feel that connection of being on the River Thames when you’re in Abingdon town centre.”

As rivers lost their historic uses, people started to forget about them as an asset or resource, it seems – but, as Glen says, rivers are being rediscovered. “You’re not using the river for the same purpose as in the 18th and 19th centuries, when it was about transporting goods for economic reasons. But there is a lot of evidence proving that waterways benefit people’s health.

“Rivers can also bring people, and therefore income, to a town or city. People enjoy natural assets, particularly rivers, and I think it’s also good economically for the town to reconnect where possible. If you say ‘let’s go for a drink somewhere,’ you might say ‘let’s go to that new pub with the terrace that’s opened up on the river.’ It’s almost second nature to us to choose an attractive riverside location where and when are able to do so.”

Making rivers more attractive to people

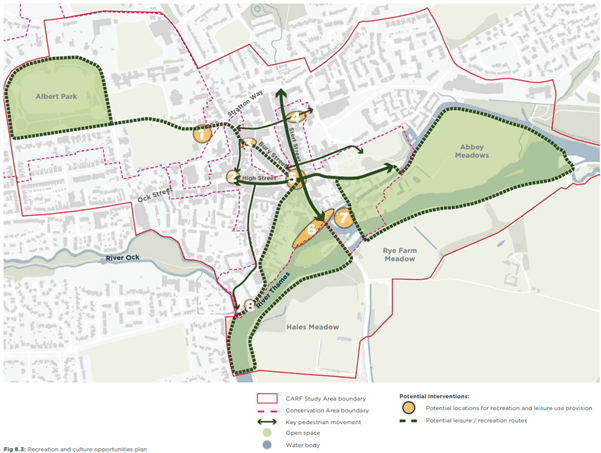

Glen says: “In Abingdon, we were keen to better connect existing walking routes along the river and redevelop plots of land that aren’t just for private use or road space for example, but could be used for communal spaces such as a pub/restaurant, play area or cafe.” Sometimes there are plots along a river that are publicly-owned or, in some case cases, can be compulsorily purchased to create a community asset, Glen explains.

In central Abingdon, Carter Jonas found the land alongside the river was mainly being used by joggers and dog walkers and so not to its full potential. Through consultation it was found there was a lot of local support for walks that could link the historical part of the town and recreational facilities with the river. The walks could be signposted from key locations in the town in order to create an “historic walk” and, in so doing, include the River Thames.

Glen suggests some of the narrow roads alongside the Thames could be pedestrianised, at least some of the time. “You don’t need cars on this river all the time. Some of the riverside roads are very narrow. So long as people can still get to their property, a road doesn’t always need to be a through road,” he says.

Other ways of bringing people to the river are events, such as festivals and races. Glen says: “The town could have events along this part of the river. In addition, where a site has potential for development, an accessible public space can be included.”

There is a myriad of uses for a river, from living on a narrow boat, to cold water swimming and rowing or taking river tours, Glen points out.

The challenges and how to overcome them

Glen explains: “Abingdon has grown away from the river because historically it was prone to flooding. In centuries gone, the town builders avoided the floodplain of the Thames because of regular flooding of the banks of the town. It is simply a fact of life when living along a river which is prone to seasonal changes in level.

“Builders clearly have to raise floor levels to avoid being flooded regularly.” Glen gives examples of where land has been raised, such as alongside the Thames in Richmond. “When you seek planning consent you must also prepare a flood risk analysis and identify a method of building with raised floor levels, and avoid ‘sensitive’ uses of the land, such care homes or detached homes on ground floor levels,” he says.

“You identify which sites work in areas of flood risk – and which just will not. Clearly, planning and environmental regulations make clear that you can’t have sensitive uses like residential living or at least, if you do, have requirements for raised floor levels in order to be considered habitable and safe. Although with requirements to plan for one in 100-year flood levels plus climate change, it can be challenging for engineers and architects to design in such scenarios. The key is you have to full assess and understand the risk and manage it.”

Glen points out that while reconnecting to rivers is “not a quick and easy thing to do,” it is worth it. He points to the splendid views and settings which often exist along a river, especially when spots that are unused or derelict are replaced with something more attractive and accessible.

Is it always appropriate to use the river in a regen scheme?

“No,” Glen says. “If you’re in more of an industrial-based town that never really used or connected to a river culturally, or one which hasn’t historically developed around the river, it will probably be very challenging to reconnect to it.

“But in a town like Abingdon, where it’s already got a lot going for it,” he says, “you should seek to capitalise on your strengths. And the idea of reconnecting to the River Thames is really just doing that. While we proposed several other important strategies to improve the town centre, reconnecting it to the river seemed like one good idea long term.”

Successful use of a river in regeneration

“You have to be an opportunist,” says Glen. “You have to be the kind of really creative opportunist who can work well with a range of local groups and authorities. Any strategy to ‘rediscover’ a local asset like a river needs to be a joint venture between councils, for example a Rivers Trust, the community, the local council, and any affected landowners.”

Carter Jonas has also developed strategies to better connect to waterways such as in Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, and at the same time improve disadvantaged areas of the town: “One was Hall Quay in Yarmouth, where historically (even back to Saxon times) herring used to be unloaded along the River Yare. Another involved redeveloping a route from the rail station to the town centre using a bridge link over the river. Norfolk County Council was also keen to improve connectivity to the town, and central government provided funding to do so. Last year a new bridge, the Herring Bridge, over the River Yare was opened in Great Yarmouth.”

He also mentions Newcastle as a good example of the River Tyne being used well, with its numerous walkways, restaurants and bridges. “It’s a really interesting part of the city,” says Glen. “A lot of people gravitate down to the river simply because you can enjoy the sites and views, and just go for a pleasant walk. People just want to connect with The Tyne.” It is of course well known that the River Tyne has been vital in Newcastle’s history, not least as it had an important shipbuilding industry and industrial heritage.

Finally, Glen observes that the potential for a town’s re-connection to its river lies with local authorities taking the lead. In so doing, they need to work closely with the community, with river authorities and conservationist, and also with landowners, developers and experienced consultants, as Carter Jonas did in Abingdon. Following such an approach, towns may have an opportunity to successfully breathe new life back into their centres and reconnect with what perhaps was once, and can continue to be, one of their most important resources.